My name is J. Eik Diggs. I got my start as a K-12 educator in 2012 teaching Spanish in elementary schools in Minneapolis, Minnesota. After receiving my Masters in Second Languages and Cultures Education from the University of Minnesota - Twin Cities, I was hired to teach and design a Spanish as a Heritage Language program at a high school in South Minneapolis.

What started as one class of 14 students developed into a multi-year program that centered ethnic studies, the arts, identity work, and youth participatory action research. Following my teaching stint in Minneapolis, I moved to Tucson, Arizona, where I received my PhD from the University of Arizona’s College of Education in Teaching, Learning and Sociocultural Studies.

I now work as an educational consultant and coach supporting teachers and administrators who are looking to start and sustain heritage language programs, as well as other content teachers committed to growing and transforming their classroom practices.

My approach to

heritage language teaching and learning

In response to the widely-accepted ideologies that have a linguistically constraining and silencing impact on students, I chose to turn to student-inquiry and racial, ethnic, linguistic and cultural representation as drivers of curriculum design. I encouraged students not to always remain in one language or the other, but facilitated and modeled language meshing and blending for engagement in class discussion.

“Write in the language or languages in which you feel most comfortable, and we’ll go from there,” was something I often found myself saying in front of my class of high school heritage language students.

I found that flipping pedagogical priorities around literacy to accommodate and affirm students’ varying entry points, yielded the results in terms of production that traditional models promised. In retrospect, coming to this realization was the beginning of a dramatic shift in my approach as a language educator.

My experiences as a heritage language classroom teacher, together with my research surrounding Black feminist pedagogies that affirm Black, Latinx, indigenous and other multilingual students of color, form the bases of my philosophies of language, literacy, and student-centered education.

Grow Your Own Programs & Youth Work

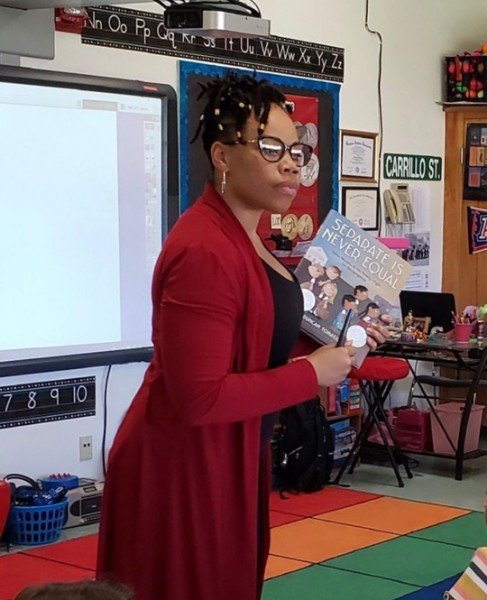

While pursuing my doctorate in Tucson, I lead the teaching and development of TUSD’s Each One Teach One - a year-long, Grow Your Own Teachers program for high school juniors and seniors of color interested in exploring education as a career. The course provided the unique combination of the study of educational models affirming of the identities of students of color, as well as the opportunity to develop lesson plans around those learnings and practicing them in Tucson area elementary and middle schools.

The structure of Each One Teach One was inspired by the work of a high school Latinx heritage language and ethnic studies class in Minneapolis, MN. After asking why meaningful ethnic studies content like the 1968 East LA student strikes and the Bracero Program had been left out of their academic experience, students decided to respond with direct action by designing lesson plans about topics they wish they would have been taught about in elementary school and teaching 3rd, 4th, and 5th graders in Minneapolis. These students created roadmaps for other young people with a desire to do the same.

Here are some highlights of that trailblazing group at work:

Focus on Identities:

Teaching language and literacy through identity exploration and self-definition is foundational to my work with students and teachers.

Identity texts are student products that are created multimodally, reflect their lives and realities in a positive light, and are meant to be exchanged with peers and other audiences (Cummins & Early, 2011). Using identity text in your teaching fosters confidence in your students and bolsters their literacy skills.

When Black, Latinx and other students of color are supported in “creating and manipulating the tools of representation,” though identity text work (Hernandez, 2020), they share beautiful, intricate, mosaic colleges of the self, creating new possibilities for the definition and articulation of their multifaceted identities.

Identity work is also part of our Black feminist traditions. I have learned a lot from Audre Lorde (1984), who taught me that identities are composed of both unique and overlapping parts. When you combine these parts, you create a coherent whole - like a collage of the self. These self-parts are never static. There are infinite factors and variations happening over time and space (Alexander, 1994).

My approach to identity texts with multilingual/heritage learners honors that by not choosing just one aspect of our identities at the expense of others. And honoring identity work as important acts of resistance to deficit narratives and harms young people have experienced.